Technology is poised to change the traditional farm. | Reuters/Chaiwat Subprasom

Today’s technology is rushing into one of the last traditional industries: agriculture.

A field largely still unaffected by the technological revolution, farming is ripe for change as need couples with opportunity.

“We’ve seen a wave of technology impact our information industries,” says Stanford Graduate School of Business professor Haim Mendelson. “Now we see another big wave of technology reshaping our traditional industries, and certainly agriculture is one of the most basic ones.”

Driverless tractors tilling acres of crops, produce growing in massive climate-controlled warehouses, and seeds genetically altered to require less water are among the high-tech innovations changing, or about to change, agriculture. These technologies are making farms smarter, more productive, and increasingly efficient.

And as technology reshapes the field, the benefits will compound. “This is one industry that everybody needs,” Mendelson says. “Everybody eats. So changes that improve productivity for a relative small number of farmers will scale to help everyone.”

In a new paper, Mendelson, with co-authors Stanford GSB professor Hau Lee, Value Chain Innovation Initiative Director Sonali Rammohan, and 2017 Sloan Fellow Akhil Srivastava, show what trends are pushing this food revolution and highlight the areas that are increasingly attracting startups and investors.

Changing Needs

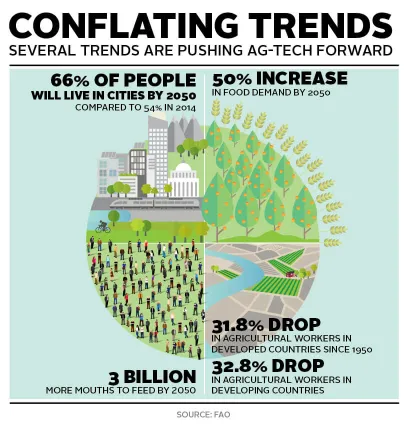

The world’s food system is desperate for an overhaul. By 2050, studies show, the world will have 3 billion more mouths to feed than it does today, and demand for food will rise by 50%. More of those people will live in cities, much farther from the traditional source of food — rural farms, says Josef Schmidhuber, the deputy director of trade and markets at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Exacerbating the problem, climate change will put more demands on how food is grown, while fewer people will work in the farming industry.

“While technology is by no means a panacea,” Mendelson says, “it offers opportunities in an internet-connected world.” Technology, he says, can create a more productive, efficient, sustainable, and resilient food system.

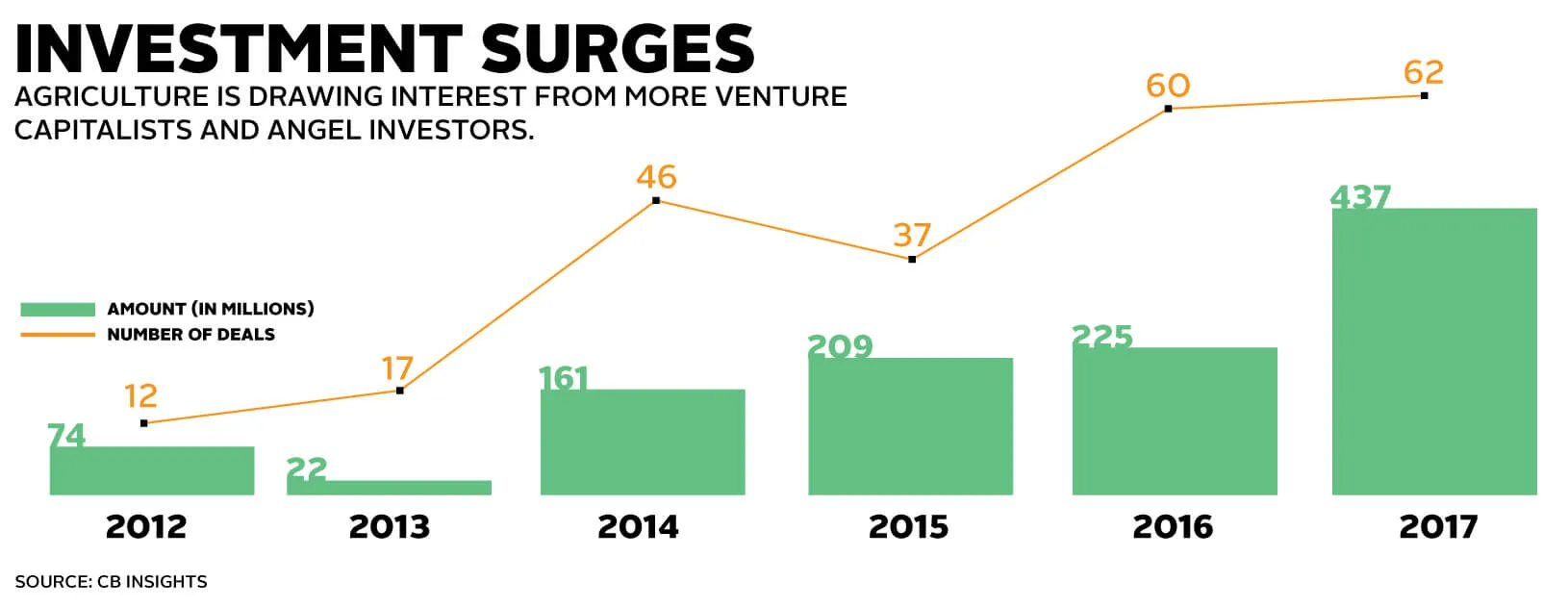

Although investments in the agriculture sector might seem like seedlings in comparison to overall VC funding, venture capitalists and angels are increasingly looking toward farming as an investment opportunity. They poured $735 million into 147 deals in 2017, according to CB Insights. That’s a jump from $57 million for 71 deals in 2013.

In addition, more of these startups are getting snapped up by big farming conglomerates, which are building out their own agtech divisions. For example, farming equipment giant Deere & Co. has an intelligent solutions group focused on precision agriculture that employs over 300 software developers, engineers, and testers. Just last year, it bought precision agriculture startup Blue River Technology for $305 million. Monsanto completed one of the largest acquisitions in the space when it bought big data company Climate Corp. for $1.1 billion in 2013.

Biggest Opportunities

For startups, the low-hanging fruit is analytics, Mendelson says. These include monitoring technologies and data analytics that can make sense of satellite monitoring or weather simulations. A major area is precision agriculture, which involves collecting and analyzing data at the individual plant level. According to the Stanford GSB team’s research, a survey of American farmers who used precision technology reported average cost reductions of 15% and a 13% increase in yields.

Beyond precision farming, analytics can be used in more general monitoring tools and centralized digital platforms. For example, Ceres Imaging, launched by Stanford graduates, helps farmers collect field irrigation and fertilizer data through sensors and cameras attached to small planes. Startups in this category have raised about $825 million from investors, Mendelson says.

Automation technology will continue to vastly change farming. Just as self-driving cars begin to dot freeways, automated tractors will enable farmers to work several fields simultaneously with the same number of workers — or fewer — and operate equipment day and night. Automated irrigation systems that collect information about soil and water levels will allow farmers to use water more efficiently. Startups in this category have raised $400 million.

Other opportunities Mendelson and Lee identified include:

- Product innovations ($4.36 billion in investment): New technologies such as gene editing or cellular agriculture are designing entirely new kinds of foods. Impossible Foods and Memphis Meat are bringing lab-grown meat to the local burger joint.

- Digital marketplaces ($682 million in investment): Allow farmers to lease equipment, pool together for better insurance, or connect to local customers. Full Harvest, for example, helps farmers sell imperfect but edible produce that wouldn’t find a market at the local supermarket, while Ricult helps rural farmers find loans.

- Operations software ($129 million in investment): Helps farmers make better operations decisions, track resources or productivity, and save money.

- Skills-building tools (minor investment): Includes videos, hotline voice services, and mobile apps that help farmers share experiences. AgriFind in France, for example, is a social networking platform for farmers to ask questions and offer advice.

- Resources ($755 million in investment): New irrigation systems deploy highly targeted water and fertilizer, using less of each, while vertical and urban farms use less land and reduce pesticides.

In the long run, one single technology won’t have the most impact, Mendelson says. “It’s really the combination that will create the real value.”

Still, for an industry that lags behind others in adopting technology, the challenges go beyond investment dollars flowing into agtech. Smarter farms also require smarter workers who can operate the new technology. And business and government regulations, trade and tax policies, and even basic technology infrastructure must support these innovative farming techniques.

There is also something less tangible that no policy can change, he says.

“Probably the biggest challenge is the fact that people like doing things the way they used to do them in the past,” Mendelson says. “This industry was not a leading user of information technology, and as a result of that, you need to change the mindset.”

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.