Silicon Valley Bank customers speak with representatives of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in Santa Clara, California. | Reuters/Brittany Hosea-Small

Things have moved quickly since Silicon Valley Bank imploded last Friday in the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history. Federal regulators rushed to take over the midsized lender favored by tech startups and venture capitalists and guaranteed that all of its depositors would be made whole. President Joe Biden reassured Americans that his administration would “do whatever is needed” to ensure their money is safe.

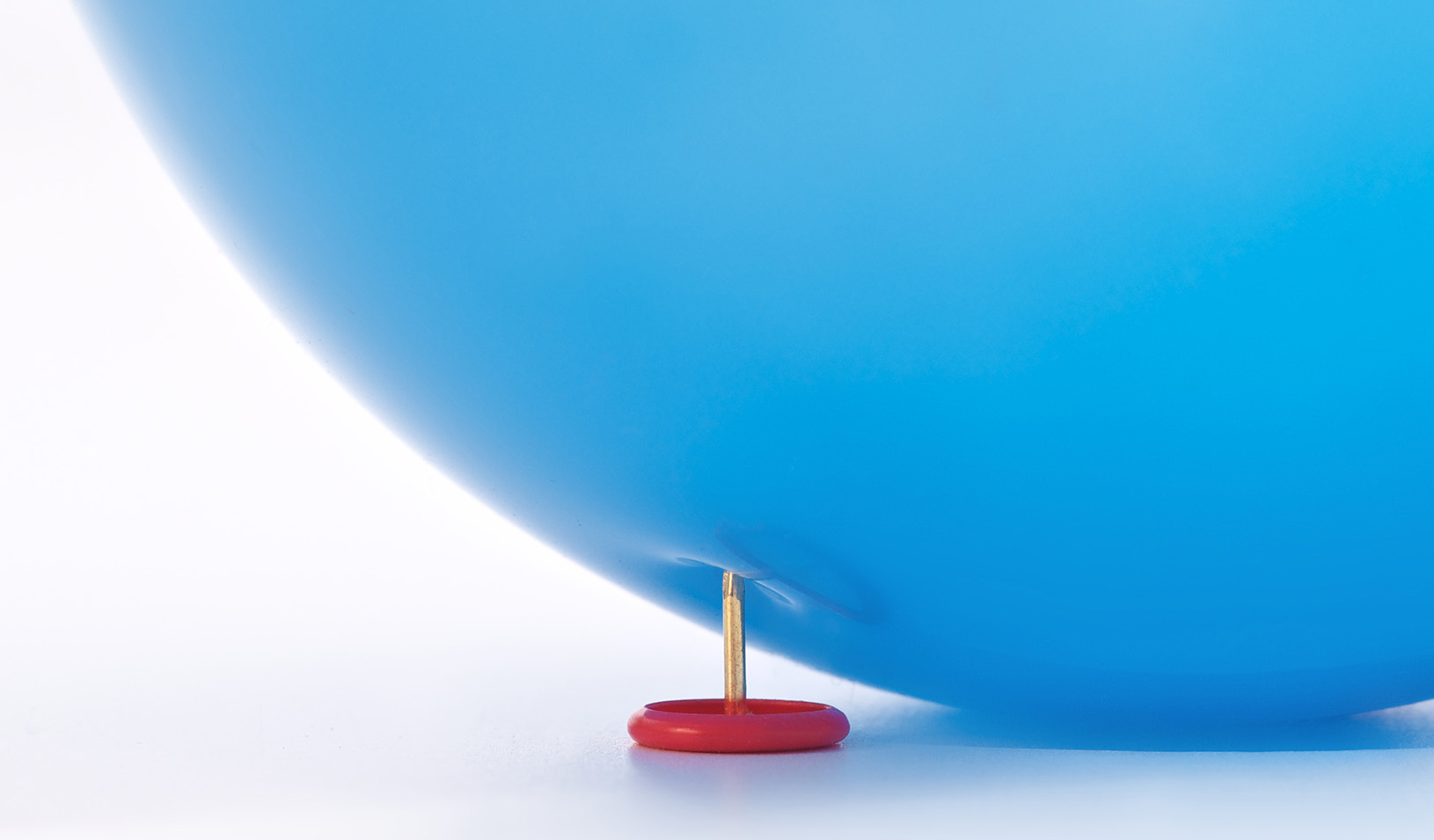

The collapse of SVB (and Signature Bank soon afterward) has left investors jittery and raised concerns about the stability of banks that aren’t “too big to fail.” And it’s set off an avalanche of post-mortems, finger-pointing, and perhaps, soul-searching.

For more perspective on this unfolding situation, we spoke with four professors of finance at Stanford Graduate School of Business: Anat Admati, the author of The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What to Do About It; Juliane Begenau, whose recent research looked at banks’ capital requirements; Paul Pfleiderer, who (with Admati) has written about overleveraged and underregulated banks; and Amit Seru, the coauthor of a new paper that examines the risk of more bank runs like the one that brought down Silicon Valley Bank. They spoke about SVB’s not-unpredictable troubles, regulatory failures, the state of the American banking system, and the unintended consequences of rescuing uninsured depositors.

A Crash Course on Interest Rate Risk

Anat Admati: The mortgage crisis in 2008 was mostly about credit risk, bad mortgages, and, well, also some deception. Silicon Valley Bank’s losses had more to do with interest rate increases. The bank invested quite a bit of money in long-term government bonds that are safe in the sense that they won’t default. But when interest rates increase, the value of such bonds declines, and the longer the maturity, the more bonds are affected by interest rate changes. When I taught basic finance courses, we covered this material routinely.

Juliane Begenau: It’s not brand-new information that if you invest in long-dated securities, the valuation of those securities is sensitive to discount rate changes. An interest rate shock can lead to a decline in the market value of assets. It might not wipe out all equity and cause a full-fledged banking crisis, but it can lead to significant losses. That’s what happened at Silicon Valley Bank.

I’m glad that people have been made aware that interest rate risk is a real thing. It was fairly clear that some banks had these large unrealized losses. Yet somehow, only last week people panicked about it. The markets were not worried about this until they were finally worried about this.

Could More Banks Be in Trouble?

Amit Seru: In our new analysis of all U.S. banks’ exposure to the recent rise in interest rates, Silicon Valley Bank is not an outlier. Lots of banks have had a bad shock. We calculate that the average U.S. bank’s market value of assets is about 9% lower than suggested by their book value.

Typically, a regional bank doesn’t have as many uninsured depositors as Silicon Valley Bank. That was unusual. But there are lots of other banks out there where the losses are pretty high and you do have a reasonable proportion of uninsured depositors. You can take those asset losses and feed them to the liability side and ask, “Suppose these uninsured depositors have the first stab and leave without any impairment because they can ‘run’ faster — what will be left for the insured depositors, who given their insurance tend to be more ‘sleepy’?” Then you can figure out which bank is insolvent, with its equity wiped out, and where the FDIC [Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation] will have to come in and pay to make insured depositors full from their fund.

Begenau: It would be possible for banks to be better capitalized. Yet relative to 2008, banks — especially the largest banks — are way better capitalized than they used to be. Even though banks’ leverage ratios have come down, they’re still high relative to non-financial firms. One could think about other designs of the banking system that would ensure a stable payment system and lead to the same economic functions as deposit-making, which is very important. It’s not obvious that this has to be backed by risky investments.

Containing Risk and Reassuring Customers

Paul Pfleiderer: It’s not a replay of 2008, but obviously this is a fire that everyone is interested in putting out and making sure it doesn’t spread. At the very least, the regulators should be stepping up efforts to look at other banks. You don’t want to get into this situation where you’ve got potential bank runs and you say, “Oh, the system’s all fine; don’t worry about it.” You should be very carefully looking at where the risks are and to the extent possible forcing banks to reduce unsound risk exposures and improve capital levels. This is a delicate thing to do in the current situation and you don’t want to spook the market. Ideally, you would’ve done it well before a crisis hits.

Begenau: The thing we worry about in a bank run scenario is that if everybody thinks a bank run is likely, then it’s going to be even more likely to happen. By saying your deposits are safe, regulators are trying to solve this coordination problem of keeping everyone calm. The Biden administration came out strong to say nobody should worry. We’re even guaranteeing deposits above the deposit insurance limit for the two banks that failed. I think that is a strong signal that people shouldn’t panic.

Where Were the Regulators?

Begenau: When regulators are looking at risk measures of banks, it’s important to focus not only on income-based measures but also on market-based measures. And not necessarily what the market itself assessed, because as we saw recently, the market can underestimate risk exposures in banks.

Pfleiderer: Silicon Valley Bank’s failure reinforces the narrative that we’ve been giving from the start, which is that the banks have a lot of political power and are always pushing for less regulation. There’s bad regulation, of course, but a lot of it is for the good and prevents things such as what we’re seeing right now. Silicon Valley Bank pushed very hard against having $50 billion dollars in assets be the threshold for heightened scrutiny for banks that are systemically important; it wanted the threshold to be $250 billion. And now we’re seeing that — guess what? — a bank that is perhaps strategically a little bit under $250 billion turns out to be quite important. It didn’t appear to be one of the real big banks, but it was big enough to cause turmoil.

Admati: When I say the banking system is too fragile, I am often told, “Things are just fine. It’s a good system. The rules were reformed.” Some of us have been arguing for years that these narratives are false and misleading. The failure to write proper rules in banking goes back decades.

The reform efforts after the financial crisis of 2007-09 — which was a direct result of terrible rules — have been pretty much a mess. Some were akin to reducing the speed limit for loaded trucks from 98 miles per hour to 95 miles per hour without even measuring the speed properly. Politicians and regulators are failing us. And when the flaw in the system becomes visible, as in 2008 or now, they cover up their failures and provide bailouts if that seems better than the alternatives. Then the public stops paying attention and bank lobbyists make sure the rules continue to tolerate recklessness.

The Effects of Backstops and Bailouts

Seru: In the short run, it seems okay to “backstop” uninsured depositors, and I can see why the federal government tried to do it, because you can see from our analysis that given the losses are pretty widespread and many banks have uninsured depositors, contagion would have spread. But if you look into the future, the consequences of this action could come back to haunt us.

This is exactly what happened in the S&L crisis. Interest rates went up and depositors of savings and loans started asking for a higher interest rate. On the other hand, S&Ls’ investments were long-term investments locked in at lower rates. As a result, many S&Ls had mark-to-market losses and their equity became underwater. This should have spooked the depositors (and made them run like at SVB) but the government stepped in and provided some support to S&Ls, much like the situation right now. What did the equity holders and managers of S&Ls do going forward? They said, “Let us take risky bets and gamble for resurrection — because heads we win and the risky bet pays off. If it’s tails, we were underwater anyway and it is the government that loses.”

I worry that the situation we have currently created might be similar for banks going forward. It is very difficult to monitor the risks banks take in real-time. And by the time we find out, it’s invariably too late.

Admati: The moral hazard and conflicted interests about borrowing and risks are there all the time. Backstopping the deposits reinforces the problem. Bank managers want to take more risk and reap high returns, magnified by leverage on the upside. The downside is felt much more by others. In the worst-case scenario, even when there are scandals and failures, bankers are not the ones suffering much personally.

Depositors want to be sure that their money is there. They are not in a good position to supervise the banks. Instead, they should want effective monitoring by regulators and supervisors, which is the equivalent of what unsecured lenders would have to do, maybe through conditions or covenants attached to the debt, in normal markets.

Pfleiderer: I have sympathy for entrepreneurs and anyone that had their money in Silicon Valley Bank. But given that the government stepped in, that means there’s going to be less of a push on the part of venture capitalists and others for reasonable and effective regulation. The people who had deposits in the bank don’t have to worry about it and therefore they’re not going to be lobbying for better bank regulation. That’s one manifestation of moral hazard here. It creates incentives for people not to be so concerned about banks because they know the government’s going to step in.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.