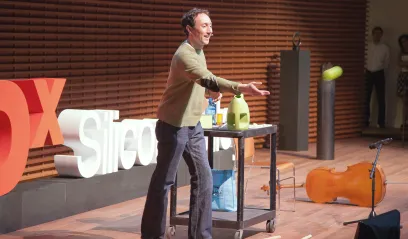

Your job as a presenter is to engage your audience, to pull them forward in their seats. (Reuters photo by Beck Diefenbach)

The first two posts in this series talked about how to remember your presentations and what to do if you do forget parts of it. Now we need to focus on the other side of the speaking equation — the audience. Specifically, what you can do to make your presentation more memorable.

Audiences need help to remember your content. Unfortunately, the norm for audiences is to “sit back and take it.” This results in unengaged audiences who are often left to find meaning in the presenter’s message. With careful crafting, you can include three concepts in your presentation that will facilitate your audience’s remembering what you say and your call to action: (1) variation, (2) relevance, and (3) emotion.

Variation — in Sound, Sight, and Evidence

Diversify your material to keep people’s attention, with variation in your voice, variation in your evidence, and variation in your visuals. (Photo by Stacy Geiken)

Your job as a presenter is to engage your audience, to pull them forward in their seats. Unfortunately, audiences can be easily distracted, and they habituate quickly. To counter these natural tendencies, you must diversify your material to keep people’s attention, with variation in your voice, variation in your evidence, and variation in your visuals. You have likely been the victim of a monotonous speaker who drones on in a flat vocal style, like Ben Stein’s character in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Adding variation in your volume and speaking rate will help keep your audience’s attention and motivate them to listen. And by speaking expressively, your passion for your topic comes through. However, for many presenters, this type of speaking is not natural. I often instruct less expressive speakers to infuse their presentations with emotive words, such as “excited,” “valuable,” and “challenging,” and to inflect their voice to reflect the meaning of these words. If you are speaking about a big opportunity, then speak “big” in a big way. With practice, you will feel more comfortable with this type of vocal variety.

Varying the type of evidence you use to support the claims in your presentation is equally important. Too often, presenters exclusively use their favorite type of evidence. You might over-rely on data or on anecdotes. But both qualitative and quantitative academic research have found that triangulating your support provides more compelling and memorable results. So, try providing three different types of evidence, such as a data point, a testimonial, and an anecdote. This triangulation neatly reinforces your point, and it allows your audience multiple opportunities to connect with your idea and remember it, which is why it’s a technique often used by advertisers to reinforce that you should buy their product.

By varying your voice and evidence, you will make the words you speak more memorable. But what your audience sees is also critical. Just as a monotonous speaker can cause mental shutdown in an audience, repetitive body movements, and slides jammed with words can fatigue and distract an audience. People are very poor multitaskers. When distracted by spurious gestures or a wall of bullet points, audience members have fewer cognitive resources available to remember the content of what you’re saying. To increase the variety of your nonverbal delivery (e.g., gestures and movement), audio record yourself delivering your presentation, then play the recording while you move and practice your gestures. Since you do not have to think about what to say, you can play with adding variation to your body movement without the distraction of speaking.

To address the issue of slides that are “eye charts” full of details in small fonts, challenge yourself to think visually. Is there an image that could represent your point in a more meaningful way? Could you create a diagram or flow chart to help get your point across to your audience? A useful tool to get your creative visual juices flowing is Google Images. Type in the concept you are trying to convey and see what comes up in the search results. The images you find might have copyright issues, so I don’t recommend using everything you find, but you’ll get an idea of the type of visual variety that is possible.

Relevance: Know Your Audience’s Perspective

As a speaker, your job is to be in service of your audience. You need to be sure that you make it easy for them to understand your message. I am not suggesting you “dumb down” your content. Rather, I argue you should spend time making sure your content is relevant and easily accessible to them. Relevance is based on empathy. You need to diagnose your audience’s knowledge, expectations, and attitudes, and then tailor your content to their needs, particularly when presenting statistics.

Too often, presenters deliver numbers devoid of context, which makes it hard for the audience to see their relevance, much less remember them. For example, I worked with a green technology company that is doing some wonderful things to save energy. During a presentation, one of their executives said their company had saved the United States 1 billion kilowatt hours of electricity. This certainly sounds like a big number, but since I am not an electrical engineer, the number means nothing to me. But then, the presenter translated this number by saying: 1 billion kilowatt hours is the equivalent of the entire U.S. not using power for 15 minutes. With this context, this number suddenly became much more relevant to my understanding, and more impactful. Clearly, context matters. By making it relevant, you make it memorable.

Another way to make things relevant is to connect your content with information your audience already knows. Analogies are a perfect tool for this. By comparing new information to something your audience is already familiar with, analogies activate the audience’s existing mental constructs, which allows for quicker information processing and understanding.

For example, when I teach the purpose and value of organizing a presentation, I often say that a presenter’s job is to be a tour guide. We then discuss the most important tour guide imperative: “Never lose the members of your tour group!” This analogy allows my students to leverage all of their experiences of being on tours to understand not only the importance of organizing a presentation, but other ideas, as well, such as setting expectations, checking in with audience members, transitioning between ideas, etc.

By focusing on your audience’s perspective and making your content relevant to them, you help them more easily understand your points, and remember those points, too.

Emotion: Give Them a Reason to Care about What You’re Saying

Most of us can quickly recall where we were on Tuesday, September 11, 2001, yet far fewer of us can remember our whereabouts on Monday, September 10, 2001. The emotional toll of the terrifying and tragic 9/11 terrorist attacks demonstrates a truism that has been known since the ancient Greeks studied rhetoric: Emotion sticks. People remember emotionally charged messages much more readily than fact-based ones. In fact, modern scientists are finding that our emotional responses have a fast track to our long-term memory. So when possible, try to bring some emotion into your presentation, whether in the form of your delivery or the content itself.

In terms of delivery, ask yourself what emotional impact you want to have on your audience. Too often, presenters focus just on the actions or thoughts that they desire from their audience without thinking about the emotional response they want. Emotions are highly motivational, so think about what you want from your audience and then be sure to present in a manner that reflects that response. In other words, your delivery style and tone need to be congruent with the emotional impact you desire. Yet at the same time, you want to be authentic and not theatrical. This requires forethought, and I recommend practicing in front of focus groups who can give you feedback on this emotional congruency.

Many of my more technical and scientific clients and students challenge me on my assertion that emotion is important. They argue that their presentations are often highly specialized and detailed, and that emotion doesn’t play a role in those types of talks. I disagree. Even the most technical talks can have some emotional aspect, especially if you focus on the benefits or implications of the science or technology. Benefits are inherently emotional … saving time, saving money, saving trees, saving lives … these are things people care about.

I once worked with a start-up company that sold antivirus software for large computer networks. Their standard presentation was loaded with facts and data points, and unfortunately most of the presentation was less than memorable. But with some minor additions that focused on protecting data and keeping users safe, the presentation became much more memorable because now it had an emotional hook.

By adding emotion, relevance, and variety to your presentation, you can be sure the audience will remember what they hear and see. The techniques and approaches I have described will also help you be more comfortable and confident in your presenting, which will only amplify your positive impact on your audience.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.