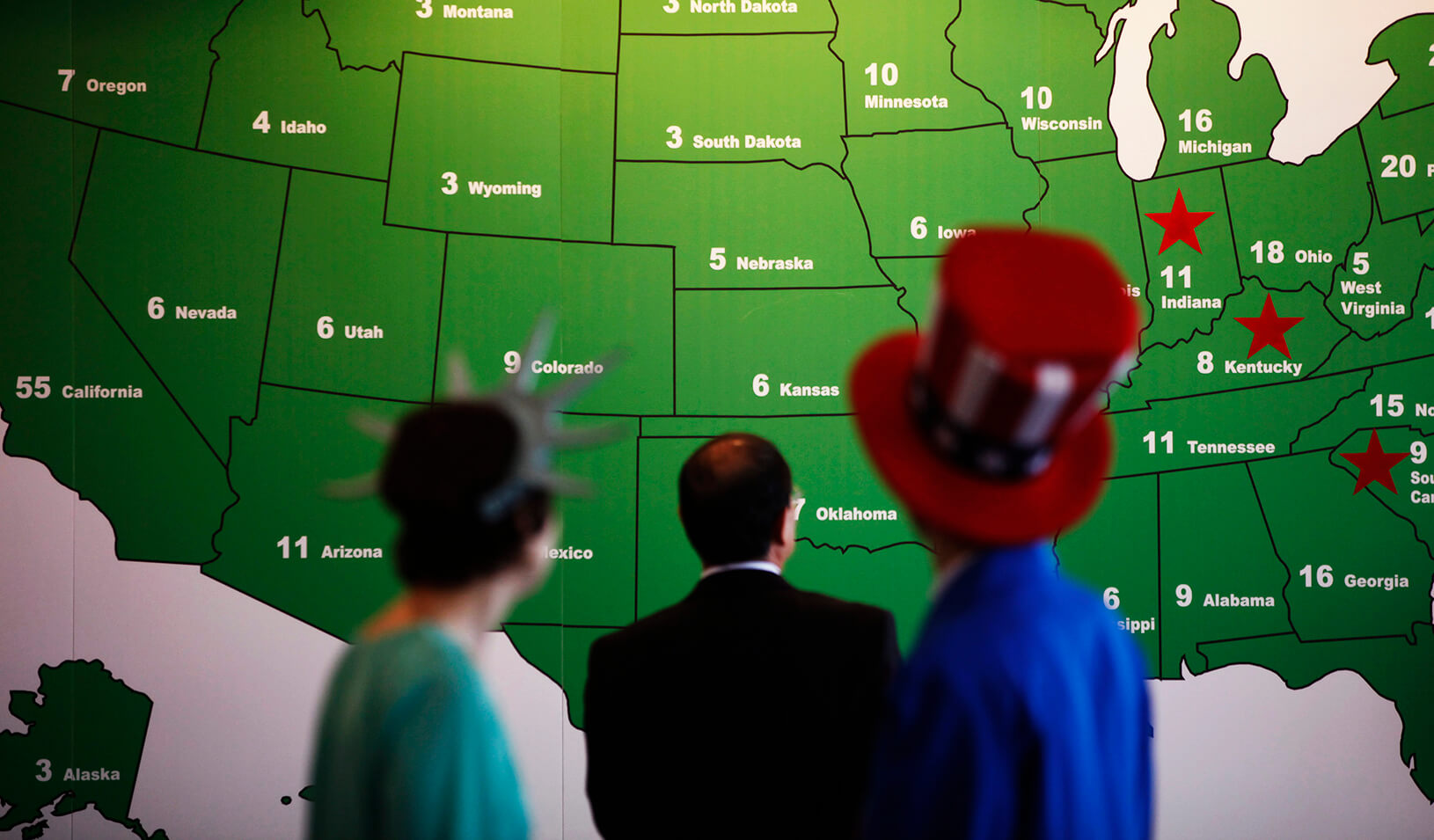

With the presidential election in the home stretch, voters in battleground states are being subjected to seemingly unending streams of ads. The video barrage is costing the two parties hundreds of millions of dollars — money spent with the expectation that repetition will drive home a winning message.

But research by Wesley Hartmann, an associate professor of marketing at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, suggests otherwise. “At some point, saturation kicks in, and you reach a point of diminishing returns,” he says. “This suggests that the significant increases in budgets will not be as effective as the money that has been spent in the past. Given the saturation in battleground states in the past, the additional effect could be quite small.”

It doesn’t take all that many ads to reach that point. In fact, it appears that it takes approximately three repetitions for an advertising message to have its maximum impact on a voter or consumer, says Hartmann. Additional ads may have an incrementally positive effect, but the costs get higher and higher.

In the presidential election of 2000, for example, George Bush spent approximately twice as much per vote on advertising in the Miami/Fort Lauderdale area as Al Gore. That’s because Bush needed to work harder to attract voters in a relatively liberal area, so his campaign saturated the airwaves. The more confident Democrats advertised less in that area, and thus garnered more votes per advertising dollar spent.

Hartmann’s earlier work focused largely on the effects of television advertising. But with a computer and smartphone in the hands of most voters, the web is the hot venue for political advertising. “Web videos that you might see on YouTube or Hulu are short, and they cut through the clutter,” he says. What’s more, many viewers step away from the television when an ad comes on, but will sit in front of the computer screen and watch an ad that precedes a video they want to see.

In a soon-to-be-published study of 21 advertising campaigns, Hartmann and his colleagues discovered that web videos are 30% to 50% more effective than TV ads containing a similar message.

Search ads that appear on the right side of a Google search page can also be persuasive. In part, that’s because when people do a search they’re generally primed to do something with the results and are open to influence, says Hartmann. A voter who searches on “Obama,” for example, could well be receptive to a message that suggests registering to vote.

Television markets are very large, making it difficult to target particular groups of voters. Web advertising, though, can draw on the huge stash of information that advertisers and app makers have collected about consumers and use it to tailor a targeted message.

If Hartmann’s thinking seems abstract, consider this: A report in the New York Times estimates that the Las Vegas television market has featured 73,000 political ads in this year alone. “I hate ‘em, I hate ‘em, I hate ‘em,” a Las Vegas cocktail waitress told The Times. Chances are, she’s not alone.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.