Globally, the top two media for advertising are television and the internet, and when it comes to the latter, advertisers spend more of their budget on paid search than anything else —more than $18 billion in the U.S. in 2013. Businesses know the position of an ad on a search results page can have a significant impact on click-through rates. But just what that impact is has never been clear.

Graph by Tricia Seibold

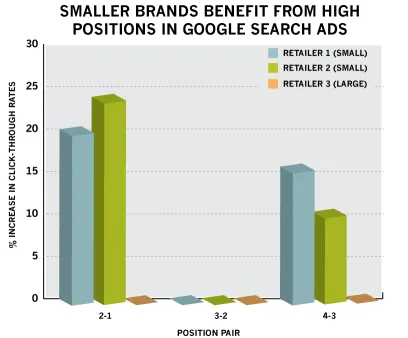

Advertisers usually assume that the higher an ad appears on a page, the more clicks it will get, and, ultimately, the more sales will be made. But new research from Stanford Graduate School of Business professor Sridhar Narayanan shows that especially for well-known advertisers, a higher position doesn’t always pay. Narayanan and Santa Clara University professor Kirthi Kalyanam found that less well-known brands benefit most from a high position because it gives them a chance to catch the consumer’s eye.

This is especially true when consumers search for a product or service for which that smaller advertiser is less well-known. “If it’s Amazon.com versus a small retailer, the Amazon ad is likely to catch our attention at any position because we recognize the brand,” says Narayanan. “Whereas a small advertiser with weaker experience with consumers benefits much more from being in a higher position.” They also found that though an ad’s position on a page can affect click-through rates, certain positions don’t have much effect at all. “It’s way smaller than correlational estimates would suggest,” says Narayanan. “Sometimes a third or a fourth as small.”

Graph by Tricia Seibold

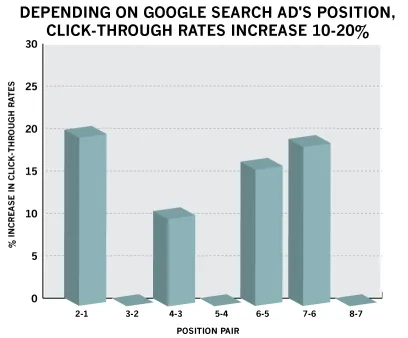

The researchers gained access to data that allowed them rare insight into the effects of position in paid search advertising on Google. “Position is the main variable firms have available to them with search advertising,” says Narayanan. “Up until now, though, we haven’t had a good way of measuring the true causal impact of that placement.”

One reason is that the placement of search ads —which appear when a user searches by specific keywords or phrases — is determined by more than just the amount of money spent. Google also decides upon an ad’s placement using its own “quality score,” primarily determined by the advertiser’s expected click-through rate and an ad’s relevancy to consumers. “If Google expects more people to click on a particular company’s ad, [that ad] gets a higher quality score,” explains Narayanan. That makes it impossible to tell whether an ad is getting lots of clicks because of higher brand recognition or a higher position on the page — or if consumers plugging in particular search terms would buy any product listed at the top of a page.

Narayanan and Kalyanam wanted to find the answer. They used Google search advertising data from four companies that had once been competitors, all large consumer product retailers. (The researchers were not allowed to release the company names or details about the category.) The largest firm, a 50-year-old nationwide chain, had acquired the other three, but for a period after the acquisition they still operated independently, with separate advertising strategies. Narayanan and Kalyanam analyzed each company’s search advertising data —information that competitors never see about one another — including bidding history, ad positions, click-through rates, sales numbers, and Google quality scores. Using an analytical tool known as regression discontinuity, Narayanan and Kalyanam conducted something very similar to a randomized experiment in order to determine the true impact of an ad’s position on its performance.

When these four competitors were advertising on Google, the top ad positions were just below the search box and the first ad on the right side of the page. The data showed that consumers click more often on the ad just below the search box than than they click on the top ad on the right side of the page. Both positions received about 20 percent more clicks than the positions right beneath them. Still, says Narayanan, this doesn’t mean that higher is always better. There was actually no increase in clicks for ads that moved from third to second position. “This is important because these advertisers were paying much more for position two than three, yet they were getting no increase in clicks,” he says.

Graph by Tricia Seibold

Ads in the third position in the right column got 10.7% more clicks than those in the fourth position. That third position is unique, says Narayanan, because it is located immediately to the right of the first organic link (not a paid ad) and tends to draw the user’s eye. The other significant position is the ad just below the point where a consumer begins scrolling down to see more links. Right-side ads that appear after scrolling are in positions five through eight; within those positions, Narayanan and his colleague found that moving from position six to five netted a 16.7% increase in clicks, and moving from position seven to six increased clicks by 19.5%. There was no increase, however, in moving up from position eight to seven.

The most significant finding, says Narayanan, is that higher isn’t always better. “When consumers already have lots of experience with a brand and its products,” he says, “being at a higher position in search results really doesn’t make much of a difference.”

Sridhar Narayanan is an associate professor of marketing at Stanford Graduate School of Business. “Position Effects in Search Advertising: A Regression Discontinuity Approach” will be published in an upcoming issue of the journal Marketing Science.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.