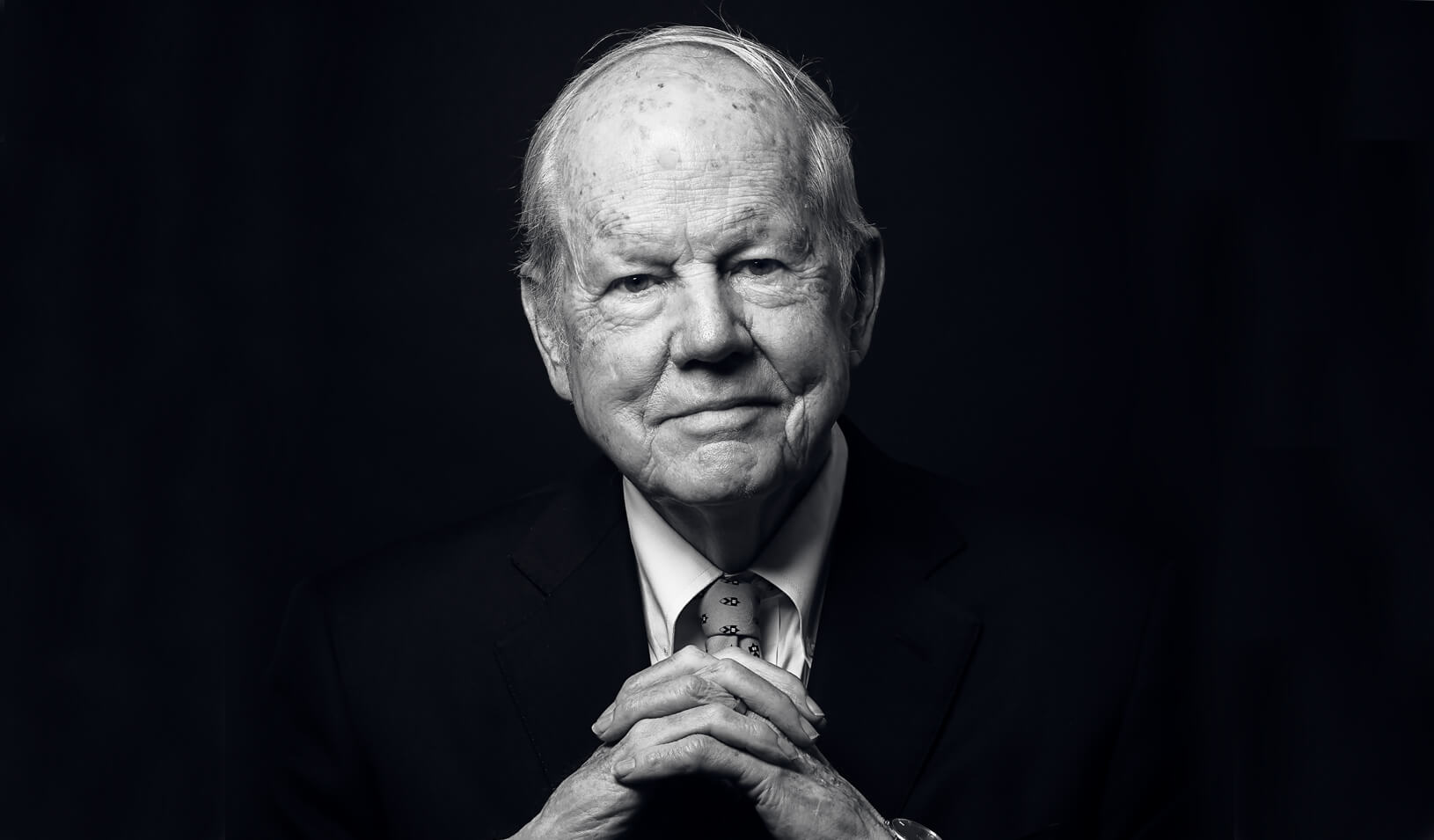

Male financial advisers are three times more likely than their female counterparts to be accused of professional misconduct. | Reuters/Larry Downing

Last year, two Stanford Graduate School of Business students launched a survey that resulted in a blistering report about systemic gender discrimination among Silicon Valley venture capital firms. Now, a new study co-authored by Stanford GSB professor Amit Seru reveals a similar nationwide bias against women in the financial industry — specifically when it comes to punishing investment advisers accused of misconduct.

In a paper titled “When Harry Fired Sally: The Double Standard in Punishing Misconduct,” Seru, writing with Gregor Matvos of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and Mark L. Egan of the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management, examined data about financial adviser misconduct and punishment.

They found that a female adviser who commits some form of misconduct — buying stocks for a client without permission, for example, or churning a client’s account — is 50% more likely to lose her job than a male adviser who breaks similar rules. Women advisers also face harsher punishment than men do, “despite engaging in less costly misconduct and despite a lower propensity toward repeat offenses,” the authors write.

“This is something that is hard to explain with rational arguments about differences in productivity between men and women,” Seru says. “Frankly, the evidence is consistent with [women advisers] being discriminated against because of some bias.”

Seru and his colleagues based their study on misconduct reports kept by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) from 2005 to 2015, which show that about 7% of certified advisers have misconduct records.

Their paper notes that men make up about 75% of financial advisers and that roughly 1 in 11 men have a record of misconduct, while only 1 in 33 women do — meaning that men are three times more likely than women to commit offenses. Despite male advisers’ higher propensity to break the rules, female offenders are not only likely to lose their jobs, but they’re also more likely to stay unemployed longer: A woman accused of misconduct is 30% less likely than her male counterpart to find a new job within a year, the authors found.

Might it be that women commit worse infractions and therefore deserve to be fired more? Seru and his colleagues looked at the data to see if indeed this was the case. But the opposite was true. “Male advisers engage in misconduct that is 20% more costly to settle,” they write.

Could it be that women are more likely to commit future offenses? Again, the data showed the opposite. “Male advisers are more than twice as likely to be repeat offenders in the future,” the study says. “These results show that firms should punish male advisers more severely than female advisers.”

Seru and his colleagues examined whether women received more severe punishment because they were less productive and thus perceived as less costly to fire. But, using the amount of assets an adviser manages as an indicator of productivity, they found women to be just as productive as men overall.

The silver lining amid all this data: There’s an obvious fix to this discriminatory trend. It turns out that the gender makeup of top management makes a big difference. At firms that are owned exclusively by men or have no high-ranking female executives, female advisers are 42% more likely than their male counterparts to get sacked after committing some form of misconduct. But at firms where the mix of male and female top executives is closer to equal, men and women are disciplined at commensurate rates.

By highlighting a heretofore unacknowledged aspect of gender bias in the investment-adviser industry, Seru says he hopes that the study might spark discussions among managers about how to eradicate such practices.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.