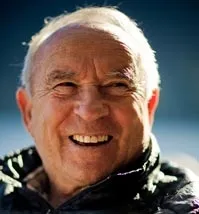

Yvon Chouinard

Figuring out what’s good for the environment can be tricky, says Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, an outdoor apparel and gear retailer committed to doing right by the planet. He points to the firm he founded in 1974, which is widely regarded as an early leader in corporate social responsibility, as an example of why it’s not easy being green.

In the 1980s, decades before Americans had widely embraced sustainability, Patagonia entered the clothing business, opening a brand-new store in Boston. The racks displayed an array of all-cotton spring items. However, within three days, many employees were complaining of headaches. The store was shuttered until officials could figure out what was wrong.

They pinpointed the store’s ventilation system, which was recycling inside air and “poisoning” employees, said Chouinard, who was shocked when told that the source of the pollution was the very clothing he considered environment friendly. Those all-cotton garments contained formaldehyde or other harmful chemicals designed to control shrinkage and make clothing wrinkle resistant.

That surprise prompted him to tour some California cotton farms, where he found land dramatically affected by the defoliant sprayed on plants as part of the harvesting process. “It was a dead zone,” Chouinard remarked, adding he didn’t even see bugs or birds on the property. The discoveries led to his decision to give Patagonia 18 months to stop using cotton produced on such farms, a radical change requiring him to co-sign on bank loans with the fledgling organic cotton farmers, some of whom called him in the middle of the night seeking emergency cash.

“It was a nightmare, but we did it. Since then we have not used a single bit of non-organic cotton,” Chouinard said. “My company basically exists to put into practice what all the smart people are saying we have to do to save this planet. We can take all the risk, and we can show corporate America it’s really not a risk at all.”

A mountain climber turned businessman, Chouinard spoke about his Ventura, Calif.-based sustainable apparel company during a talk sponsored by the Stanford GSB Alumni Association before a capacity audience at Cemex Auditorium on November 30.

While seeing its own operations expand from a tiny maker of steel pitons — rock climbing tools — to a multifaceted retailer with $340 million in sales last year, Chouinard said Patagonia has taken other steps to improve the environment. “We have 1,500 styles of clothing and shoes, and we follow every one of those products all the way from the farmer to the very end to make sure there’s no unintended consequences of our actions and it’s as clean as we can possibly make it,” he said.

Chouinard pointed to the Footprint Chronicles section of the company’s website, where consumers can read about the good and bad environmental impacts of selected products, from design through delivery. (An example: a backpack, made in Asia, is super sturdy, but its waterproof coating involves the use of a controversial synthetic chemical, perfluorooctanoic acid.)

To keep old items out of landfills and incinerators, the company invites customers to recycle unwanted Patagonia goods by mail or at the chain’s stores. And each year, as a “penance” for using up resources to make products that people really don’t need and causing waste, Patagonia donates 1% of its annual sales (net or gross, do we know?) to environmental causes, and has convinced other retailers to do the same.

The privately held firm is also one of 46 companies backing the implementation of a “Sustainability Index,” a rating that would make it easy for eco-conscious consumers to make greener choices. Proposed by Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, the initiative will evaluate a product’s environmental impact throughout its entire lifecycle. Academics, non-governmental organizations, industry groups, and other retailers are also involved in the green rating effort.

“We have to go to a different system where we consume less, but we consume better,” Chouinard said. “If consumers vote with their dollars, the corporations will have to change. I think it will make a big difference for people, and that’s what I think will turn the world around.”

Chouinard, 73, challenged the young MBA students in the audience to immediately get in the habit of donating to environmental charities. “If you’re a capitalist, you know that $10 given away now is better than $100 given ten years from now,” he said, “because that $10 starts working right now to do some good. You’ve got to start now.”

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.