Forget classifications like rock, country, and jazz — it’s time to think in terms of arousal, valence, and depth. | Reuters/Danny Moloshok

Composers have long known music’s power to soothe, energize, even provoke. Researchers, too, have observed a connection between music and mood. But which came first? Did a particular song make the listener feel better? Or does the listener feel better because he or she has a particular personality that prefers a particular kind of music?

Several years of research backed by two extensive studies involving thousands of participants convinced an international team of music psychologists that personality plays a much bigger part in musical preferences than anyone had ever imagined. Bigger even than age, gender, culture, or education.

“It turns out that personality is a better predictor of what kind of music you want to listen to,” said Michal Kosinski, assistant professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business and a member of the team. “Demographics and socioeconomics play a part, but when you look under the hood, it’s personality.”

The results open the way to understanding the connection between people, their personalities, and the music they prefer. And it has implications for both the music industry, including streaming platforms such as Pandora and Spotify, and the fields of musical therapy and health care. Data already shows that music before, during, and after surgery aids patient recovery rates.

“By studying the links between musical taste and personality, we can improve our understanding of how to use music to make people happier and healthier,” Kosinski says.

Redefining Musical Genres

Before the team that included lead author and music psychologist David Greenberg of Cambridge University, Daniel Levitin of McGill University, Jason Rentfrow at Cambridge University, and Kosinski could make those connections, however, they had to come up with a practical way of describing musical likes and dislikes.

Music psychology has long been dogged by the inability to classify music in a clear and meaningful way. Both scientists and listeners use genres to classify music, but usually the boundaries of those genres are rather blurry. Take jazz: A jazz lover could be thinking of moody blues, brassy Dixieland, or avant-garde Coltrane.

“Genres come not from scientific theory but from the ad hoc and idiosyncratic labels that record companies attach to music for marketing and publicity purposes,” says Levitin, author of the best-selling book This Is Your Brain on Music.

In addition, the choice of artists and genres depends heavily on people’s social and cultural backgrounds. Age, social class, and even geography play a part in determining whether a listener likes classical music because it’s prestigious or Chet Baker because he’s edgy. Neither is judging the music on its merits, but rather by the stereotype it symbolizes.

Greenberg, a musician, scientist, and clinician at Cambridge and City University of New York, noted that genre labels can serve a purpose by signaling a type of music, but they are far too generalized for research. “We’re trying to transcend the genres,” he explains, “and move in a direction that points to the characteristics of music that drive people’s preference and emotional reactions.”

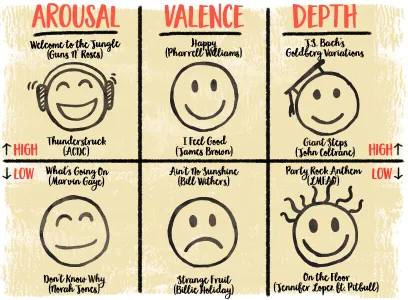

The scientists developed a common language to discern the link between melody and mood. The team asked 76 “judges” with no formal musical training to rate over 100 little-known musical samples from 26 different genres. A statistical analysis of the judges’ opinions revealed that the differences between this diverse set of musical samples could be reduced to three main dimensions: arousal, valence, and depth. Take Joni Mitchell’s “Blue” as an example. The song is considered low on arousal with its slow tempo and soft vocals, it has a negative valence because of its sad lyrics, and it rates high on depth because of the complex emotion conveyed by the harmony and Mitchell’s expressiveness.

Suddenly the playing field is leveled because a song identified as “intense” is not likely also to be described as “mellow,” just as a simple tune such as “Happy Birthday” is not likely to be called intellectually challenging, and an uplifting, marching tempo is not also a slow, mournful funeral dirge.

“The resulting musical spectrum provides the scientists with a common language to describe differences in musical style and musical preference,” Kosinski notes. “We can go beyond the superficial differences between the genres and their blurry boundaries.”

Using these tools, the entire Western world’s songbook can be mapped onto three dimensions. Forget rock, country, and jazz; try energy/intensity, mood/emotion, and complexity/sophistication. All at once it becomes easier to understand the similarities and differences between songs. One can also use these dimensions to study the link between musical preferences and personality.

Personality Test

Turning to Facebook, the researchers recruited 9,500 participants to rate their personalities and musical preferences. The group listened to 50 unfamiliar musical excerpts representing different levels of arousal, valence, and depth, and rated their preferences. They also took a standard personality test. The results revealed that neurotic individuals preferred music with negative emotions and intensity; open-minded and liberal people liked complex melodies; while those who identified as agreeable and extroverted liked songs with positive emotions.

Kosinski, who earned his PhD in psychology from the University of Cambridge in 2014 and then spent a year as a postdoctoral scholar in Stanford’s Computer Science Department, was surprised to find such a clear relationship between personality types and this spectrum of musical preference.

In the table above, the songs listed represent each of the three musical attribute clusters.

According to the team’s paper, “The Song Is You: Preferences for Musical Attribute Dimensions Reflect Personality,” today’s technology makes it easy to track what people listen to and how it affects their moods through headphones that personalize playlists, earbuds that record physiological metrics, and apps that track location and mood. If researchers can connect music to mood, linking musical characteristics to everyday behavior is next.

“Results from linking personality traits to preferences for perceived musical attributes suggest that we are the music and the music is us,” according to the paper. Greenberg adds, “Our musical taste is a sonic mirror. Through the music, we can better understand who we are and what we truly feel and believe. As a musician, I see how vast the powers of music really are, and unfortunately, many people do not use music to its full potential.”

So should we abandon current music genres and describe our preferences in terms of arousal, valence, and depth? Kosinski doesn’t believe music will ever be grouped that way by record labels or listeners. The new spectrum, however, could be tremendously useful for scientists and music platforms such as Spotify and Pandora. It also makes much more sense, he notes, than calling everything written by composers Rodgers and Hammerstein a “soundtrack” though the genre covers everything from the joyous “Do-Re-Mi” in Sound of Music to the mournful “Pore Jud Is Daid” in Oklahoma!

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.