Even if you’re not seriously injured in a major earthquake, recovering from the trauma isn’t easy. Honoring the dead, helping to rebuild, and reconnecting with loved ones all help people feel better in the aftermath of a temblor. But there’s another tactic that hasn’t received much attention: having fun.

When a 7.0 earthquake devastated parts of Sichuan, China, in 2013, researchers wondered if the use of smartphone apps could provide clues to the behavior of survivors. After reviewing the cell phone usage of more than 157,000 Sichuan residents and interviewing hundreds of survivors, professors from Stanford’s Graduate School of Business and three other universities concluded that “having fun has a special role in alleviating the negative psychological impact of disaster.”

Their soon-to-be-published study concluded that the use of enjoyable apps like online games, shopping, and music reduced anxiety, and that “too much communication — such as blanket media coverage and incessant checking of news sites — can increase the feeling of risk, make people more fearful,” says Baba Shiv, a Stanford GSB professor of marketing who coauthored the study.

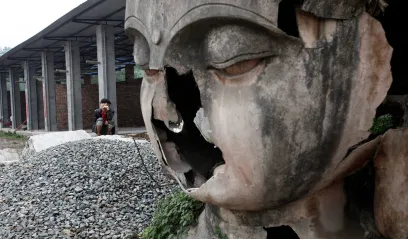

Reuters/Jason Lee

“That’s not to say people shouldn’t get information after a disaster. But we believe that the morale of survivors is often overlooked,” adds Jayson S. Jia, an assistant professor of marketing at the University of Hong Kong and the study’s lead author.

The researchers had an unusually rich trove of data to work with. Three months of anonymized cell phone records —including voice calls, text activity, web browsing, and the use of mobile apps — told them what applications people were using both before and after the earthquake. It also told them where the users lived.

The researchers linked that information to detailed records of the quake, which enabled them to determine how much shaking each phone user had endured. Finally, they conducted interviews with 800 survivors to ascertain whether they felt more or less at risk a week after the shaking stopped.

The results were striking. Survivors in areas that had the worst shaking increased their use of all types of mobile applications the most and continued that behavior for three weeks. “But only hedonic (pleasurable) behavior could reduce perceived risk, the negative psychological impact of the disaster,” the researchers write.

Although the finding that hedonic online behavior reduces feelings of risk is “statistically very significant — there’s less than a 5-in-1,000 chance we got it wrong — it is hard to map exactly how scared someone feels,” says Jia, who earned his PhD at Stanford GSB in 2013.

No Shame in Enjoying Yourself

The researchers hope their results may inspire public health officials to rethink post-disaster strategies: “We witnessed an entire population engage in psychologically adaptive activities that reduced their perceived risk,” they write. “The challenge is to also get the people who didn’t engage in as many hedonic activities to do so.”

How that might happen is beyond the scope of the study, but Jia notes that people who engage in entertaining activities after a disaster are sometimes shamed by other survivors. Rather than postponing events like football games, letting them proceed might do more to facilitate recovery, he says.

Indeed, the morale of combat troops, people with every reason to feel stressed and at risk, was improved by USO shows during World War II and the Vietnam War, Shiv notes.

The findings of the earthquake study track with earlier work on how people cope in the wake of disasters. “After September 11, 2001, for example, people reported increases in overeating and going off diets, drinking, smoking, time spent with family and friends, shopping, and church attendance,” Shiv and colleagues from Duke University wrote in a 2005 research paper.

But most work on post-disaster recovery has been based on lab studies, Shiv says. Because the earthquake paper is grounded in the experiences of thousands of people, it’s a departure. “The skeptic in me always wonders if it [the effect both papers uncovered] is manifest in the real world,” he says. “This confirmed it. And the strength of the correlation surprised me.”

“The Role of Hedonic Behavior in Reducing Perceived Risk: Evidence from Post-Earthquake Mobile App Data,” will be published in a forthcoming issue of Psychological Science. Along with Shiv and Jayson Jia, it was coauthored by Jianmin Jia of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Christopher K. Hsee of the University of Chicago.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.