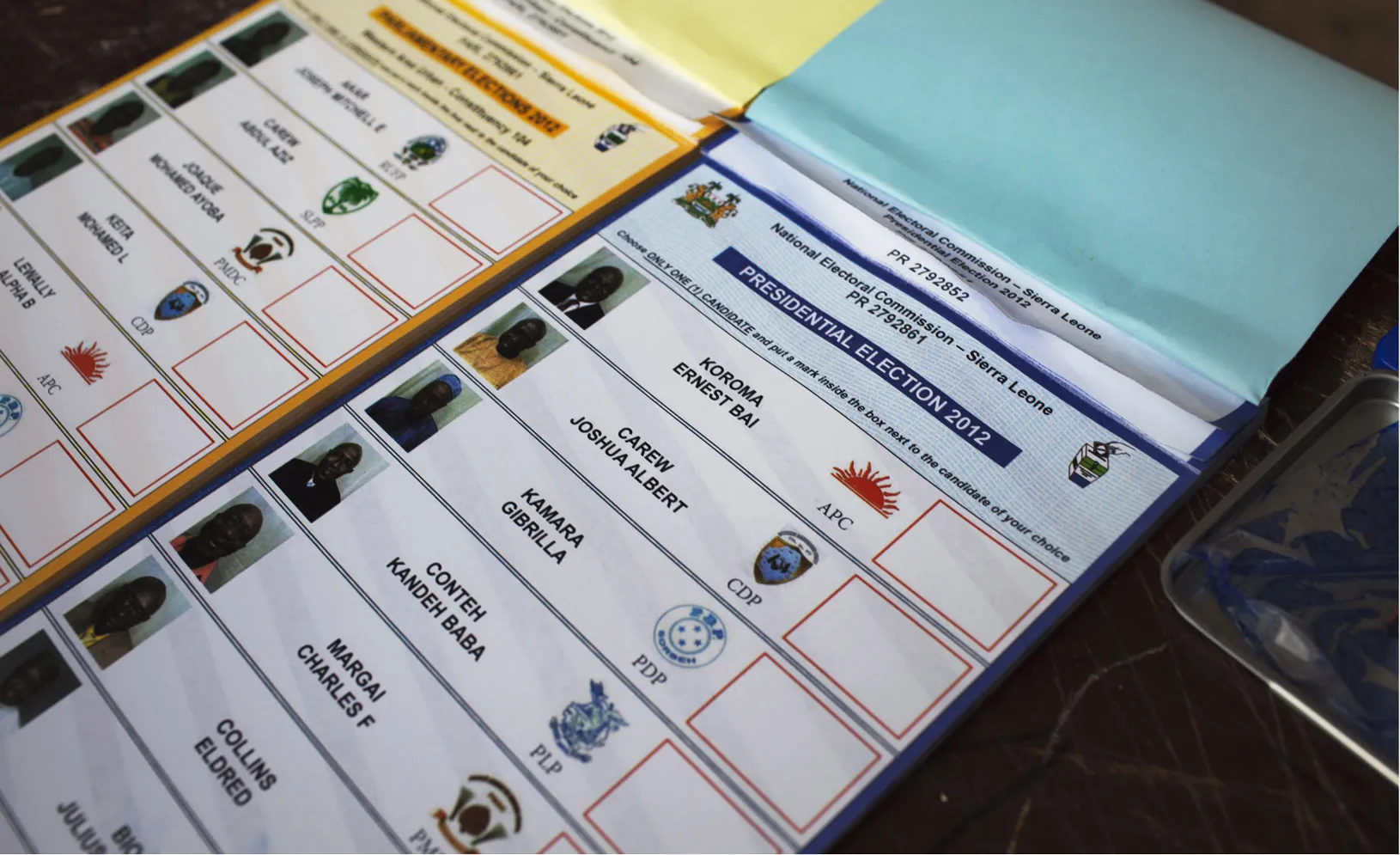

A woman casts her ballot at a polling station in Sierra Leone. | Associated Press photo by Rebecca Blackwell

With the presidential race in the home stretch, there’s little doubt that the unending barrage of polling data influences voters. But the conventional wisdom that they mindlessly follow the herd misses a critical point: Voters also look at polling results as a way to garner information they need to make up their minds.

A new working paper by Neil Malhotra of Stanford Graduate School of Business, and David Rothschild of Microsoft Research, shows that some voters do, in fact, switch sides in an effort to feel accepted and to be part of a winning team. But the paper also concludes that greater numbers of voters are searching for the “wisdom of crowds” when they evaluate poll results, and that the opinion of experts matters more to them than that of their peers.

The researchers asked a selected group of voters to state their opinions on a variety of real public policy questions, and then presented them with fabricated poll results on the same topics. When the test subjects learned that a large number of experts favored a position, opinions shifted by 11.3%. But the “opinions of people like me” changed opinions by just 6.2%, while a general poll saying that a majority of people favored one side or the other moved the needle by 8.1%.

Although the focus of the research was on how polls effect voting on policy questions, the results, says Malhotra, shed light on elections for office as well.

Voters, the researchers found, are looking for and responding to new information. As a result, polls that state what’s already well known — an extremely popular incumbent is likely to win, for example — are likely to have far less effect than those that reveal something unexpected.

“The main reason why people conform to majority opinion in the political domain is that they perceive there to be information about the quality of the policies in learning about mass support,” the paper concludes.

The researchers also investigated an intriguing possibility: Do voters switch sides to “resolve cognitive dissonance”; that is, to soothe themselves over the fact that a policy they don’t support is likely to win? But they found little evidence to support that theory.

The study offers some comfort to those who fear that polling is dangerous to the political process. “There are two ways to look at these results,” says Malhotra. “Majorities can cascade, which is not good if we want to preserve minority rights or worry about herding. But we see that people are also looking for information and try to learn from the wisdom of crowds.”

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.