In its latest issue, Stanford Business spoke with seven finance professors at Stanford Graduate School of Business about some of the topics and trends they’re watching closely.

For 100 years, we’ve been dedicated to the things that haven’t happened yet, and the people who are about to dream them up. Join us in commemorating our Centennial in 2025.

In these wide-ranging interviews, they discuss venture capital and the innovation economy, the United States’ debt dilemma, and pension funds’ risky investments. Other topics include the move toward a digital dollar and the emergence of non-bank banking. The package also features critiques of the assumptions behind ESG investing and the rules governing corporate power.

Most people associate venture capital with technology, but the reality is that the best companies that are venture capital-backed are changing the business model of their industry or ushering in new industries. Venture capital and, more broadly, investment in innovation, are expanding dramatically into a lot of fields. Now it’s difficult to mention a field or industry where venture capital is not present — robotics, medical equipment, education, law, finance, and so on. It’s pretty obvious why people should care about this, because it’s going to change their lives.

Here’s an example that I really like. CRISPR, the new gene editing technology, was developed less than 15 years ago. Now there are hundreds, if not thousands, of startups that are pursuing applications of CRISPR. That will dramatically change our lives and the lives of future generations. This is not only driven by large companies; in fact, it’s mostly driven by biotech VCs.

If you look back, venture capital is behind most, if not all, of the largest companies in the U.S. created in the last 50 years. My research suggests that up to two thirds of the companies that became very successful as a result of venture capital backing would not have existed otherwise. So if we’re really interested in what’s going to happen in 10 or 20 years down the road, venture capital is critical.

I strongly believe that decision-makers in government and corporations should pay more attention to how venture capitalists process information and how they make decisions. For example, if you go to a traditional company and say, “You’ll start 100 projects, 80 of which are going to fail,” that’s not going to go very well in a CEO’s or CFO’s office. But that’s exactly what’s happening in the venture capital business. As there is more and more disruptive innovation, decision-makers in traditional businesses or traditional organizations will benefit from learning how they can think like venture capitalists.

It’s useful to mention that right now people are talking about how venture capital is not doing well because the valuations of many high-profile VC-backed companies have declined and many of them have to lay off people. If you happened to be an investor in 2018, 2019, or 2020, you might be counting your losses right now. But if you are just about to enter the fray, that might be the best time to invest.

If you look at the history of innovation, when valuations are lower, this typically brings more innovation later on, because it’s easier to invest. If anything, I expect more investments in early-stage startups over the next 12 to 24 months. And some of them are going to disrupt what your readers are doing, whatever they do. — Told to Katie Gilbert

The U.S. has been at the core of the international monetary system for a very long time and there is a question about that sustainability. The country at the core has the following problem: Can it just supply very few safe assets? So maintain the debt at the country level, relatively small compared to its GDP. But then the problem for the rest of the world is that there just aren’t that many of these assets. Or, the country can expand the supply of safe assets a lot more but potentially enter a place where it can suffer a self-fulfilling crisis. This is called the Triffin Dilemma.

Which of these options will the U.S. choose? Will it always play it safe or will it actually take some risks? A few years ago, my colleague Emmanuel Farhi and I explained that there are reasons to believe that the U.S. might decide to play it risky. When we first wrote this, people thought it was a bit crazy. The U.S. had been at the core of the system for so long and its debt-to-GDP ratios weren’t so high. But if we fast forward just a few years, this has now become a bit more of a mainstream topic.

While we’re nowhere near a debt crisis in the immediate future, this is now something that economists have to think about going forward. What I think is more worrisome is that there isn’t any particular plan for bringing the debt down. At some point, we’re going to need to have a conversation, policy-wise, about how to avoid getting to a place where this becomes a real, immediate concern.

My own work tells me that when this crisis occurs we tend not to see it coming. If you look at historically big crises of the monetary system, like in 1971–72 with the collapse of Bretton Woods, the system seems to work until it doesn’t — and when it doesn’t, it goes down very fast. In some sense, the edifice of the international monetary system is built on reputation and confidence and these things tend to evaporate very quickly.

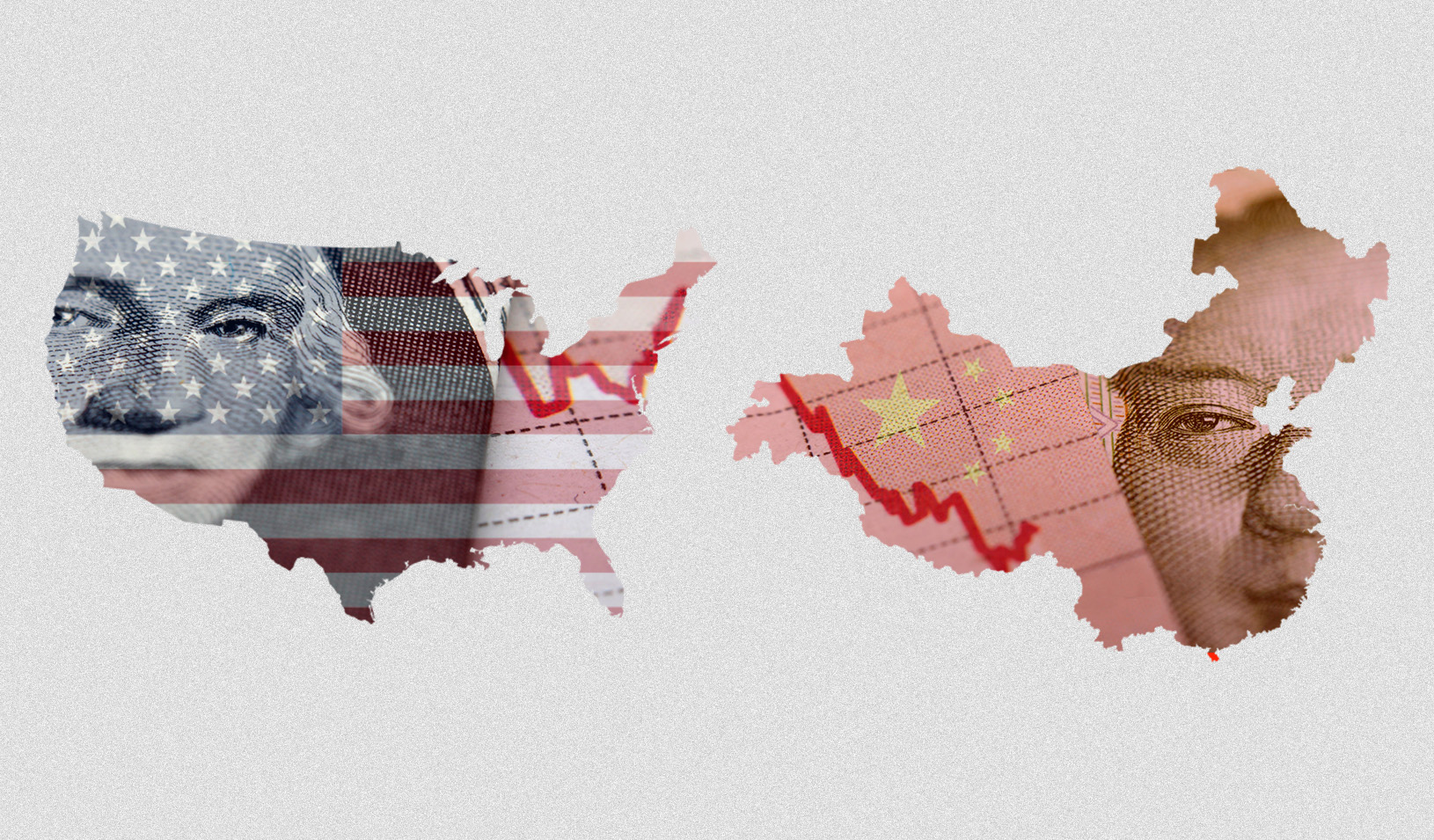

Now what happens if there’s another country that might want to play this core role? China’s government has stated that it would like to play a role in the future similar to the U.S. in terms of providing a reserve currency. This is clearly far into the future, but China has some of the characteristics that make it at least a potential candidate.

There have been many contenders for the role of the U.S. over the last 70 years and most of them have failed to displace the U.S. Some of my recent work looks into these attempts, in particular in the current context of China, and shows why they tend to often fail. Although that doesn’t mean that on the way there, China is not going to have a large impact on global markets.

And so these two topics are connected. These are two big countries, one at the very beginning and one at the very end of the reputation cycle, and their interplay is likely to shape global markets going forward. — Told to Dave Gilson

We’ve been in this private equity boom during the last few years. A lot of firms that wouldn’t pass tighter scrutiny got funding for all sorts of projects. It’s pretty shocking how much money flew into this industry without real evidence.

I’m very interested in analyzing the consequences of leveraged investors that use opacities to hide risk. Private equity promises high returns with no risk — because we don’t see the risk. It’s not mark to market because they’re buying firms and you only know what the true value is once they sell off the firms, maybe 10 years later. It’s unclear.

In private equity, the standard buyout model — buy little firms and then put on a lot of leverage and then make them public or sell them off — is way less transparent. We looked at some of these contracts and I would not know how any reasonable person could deduce what fees they were on the hook for. Yet even within private equity, there are differences: Venture capital funds have much more transparent contracts.

A lot of pension funds are desperate to get higher returns and invested in private equity. My sense is that likely they’re not getting the best deal that they could get if they were better educated and knew better what are the underlying risks. I think of pensions as institutional retail investors; retail investors are often not as financially sophisticated.

In one recent paper, my coauthor and I found that better fee contracts were available to different pensions from the same private equity fund. In this case, we don’t know how much risk they’ve taken, so we don’t know what the fair return would be. Therefore we don’t know the profit share that private equity is taking out and if it’s fair for the investors or not.

We have a new paper that we are developing where we try to explain why certain public pensions invest in private equity. It’s really hard to explain by fundamentals. It’s likely related to, well, your chief investment officer just thought that private equity is awesome.

I think big changes are inevitable, especially if private equity wants to expand. I think there is a role for private equity, but there need to be certain protections in place. That’s what the Securities and Exchange Commission is trying to do. SEC chair Gary Gensler even cited our paper in 2021 when he talked about the need to protect investors such as public pensions.

There is also a possible cost if you enforce transparency: Some private equity firms find it more difficult to compete and may no longer provide access to public pensions. The question is, how large is that cost? What about the benefit to public pensions that make decisions that are more financially sound?

I don’t think that decisions under opacity should be the guiding principle. But somehow in this area, people are content to make decisions in opaque situations. While I can see some benefits, I think we are lying to ourselves a little bit. — Told to Katie Gilbert

The Federalists said, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” They went on to say that the challenge is to give the government power over the governed and then force it to control itself. That’s why we have a Constitution and a First Amendment — these are constraints on government.

My variation on that, with respect to business and capitalism, is that we want to give corporations the right to exist as legal persons and give them enough rights so they can innovate, produce great products, provide employment, and serve society. But we need to make sure they don’t control the law and its enforcement.

Governance is about trust; it’s about accountability. Without legal institutions, markets and the economy can’t work. In sports, we accept “no rules — no game” and the need for good referees to enforce the rules. There’s no market without rules and enforcement, whoever makes these rules.

Tariq Fancy, the former chief investment officer for sustainable investing at BlackRock who’s kind of a whistleblower on ESG, recently spoke to my class and at an event entitled “CSR + ESG = BS?: Straight Talk on Business for Social Good,” in which he argued that stakeholder capitalism, corporate social responsibility, ESG — these efforts to convince managers and investors to care about other stakeholders — are harmful distractions. I would say the heated debate around whether corporations should take care of society’s needs is clear evidence that the rules of the game are not working for society.

The only way we can truly deal with climate change and other problems is to make sure that the government sets the rules of the game properly. Voluntary action, however virtuous, will not take us far enough. It’s limited by the way the system actually works, people’s incentives, and the power of the status quo.

Viewing the government as inherently evil becomes self-fulfilling because we end up destroying the government and making it so it doesn’t deliver. The narratives that somehow rules are bad and that government shouldn’t interfere with “economic freedom” have been harmful. The capitalist-socialist labels prevent a real discussion about how our institutions should be governed so that the people with power, in the government and in the private sector, will do a competent job and be held properly accountable if they fail society.

I believe that business schools have been somewhat complicit in promoting the false notion that “free markets” exist in nature and ignoring the tough challenge of creating better rules to balance competing interests and to have a social contract that holds society together.

We must think collectively about the institutions of democracy and how to, essentially, give power to truth and avoid situations in which beliefs get corrupted by confusing noise and narrow, highly resourced interests. And we should definitely question the role of money in politics. I think the fact that there’s a sense of crisis is rather helpful. Sometimes, out of crisis comes better understanding. — Told to Alexander Gelfand

There’s a hotly debated question among academics, practitioners, and regulators, which is: Are banks special? Regulators think banks are really special and give them all this nice stuff — they let them take deposits, which other entities can’t do; they guarantee their deposits and give them implicit guarantees. So banks can get cheap financing through deposits and turn them into loans in a way that other companies can’t. The thinking is that there’s something magical about the banking system, and we need to take care of these guys.

The rise of shadow banks has allowed us to test whether that’s true, at least in mortgage lending. But there’s a catch. The non-bank mortgage originators, and the fintech-enabled version of those, such as Rocket Mortgage, are originating mortgages where, for a bunch of reasons, the U.S. government has taken all the risk off the table. There’s no complicated underwriting to do. Thus, the value that non-bank originations and their fintech cousins bring is to avoid some of the regulatory requirements imposed on banks and to make the origination process convenient and easier for customers. It turns out that customers are willing to pay a small premium for that convenience. But they’re solving a marketing and customer-acquisition problem, rather than a deeper financial underwriting problem.

A lot of the activity that’s moved away from banks is similar. It’s the easy stuff. So far, the fintech companies haven’t been able to displace a lot of traditional financial intermediaries. Their business model requires them to be capital-light and that limits what they can do. In contrast, banks have that government-guaranteed deposit funding, which allows them to underwrite these assets and hold them on the balance sheet — in other words, to eat their own cooking.

The doomsday scenario for the legacy American financial system is if these tech companies figure out how to get deposit-like assets. That’s what happened in China. Alibaba, the Chinese counterpart to Amazon, had an app that everyone used for making payments. It introduced a money market fund that offered significantly higher rates than banks were allowed to offer. A whole lot of deposits left the banks — until the Chinese government intervened and made it stop, because they worried that it was destabilizing the banking system.

The nature of these innovations is that they arrive suddenly. It’s the kind of thing where you flip a switch and everything changes.

Do I think it’s a good thing? Yes. There are financial stability issues that we need to think through, but a system that’s dominated by depository institutions with all these subsidies and guarantees from the government is not what we should want. We want a free market. We also want a system where it’s OK for players to fail, and a lot of the banking system is too big to fail.

Going back to the mortgage example, shadow banks grew largely by refinancing mortgages as interest rates kept getting lower. But now, with interest rates rising, that demand has disappeared and all of these companies are no longer profitable. Many are out of business. And you know what? That’s fine. If an activity is no longer profitable and we stop doing it, that’s the right outcome. We can let them fail without the system collapsing. — Told to Edmund L. Andrews

There are many decisions that maximize shareholder value that may have social costs. But to expect shareholders to bear value-reducing strategies just for social costs is highly naive. That is not how people behave. People don’t often do things that hurt themselves for the public good.

Anytime the shareholders’ interests and other interests are aligned, we don’t have to talk about it — it’s a boring subject. If adopting environmental goals maximizes the value of the stock, the net present value of the company, we don’t have to talk about it. Everybody is in favor of that. What that means is that if you claim that doing something that’s going to help the ESG rating of the firm is going to increase the value of the firm, then you are also saying the current managers are not doing a good job. That is a big claim, and claims like that need justification. You can’t just say “I can increase value”; you need to provide some evidence.

So if you are not claiming that current management are incompetent, you need two things for an ESG investment strategy to work. You first need to change corporate policy, and that’s going to be value-reducing. You also need the corporation to have market power. Because if it doesn’t, and it’s a competitive market, somebody else will just step in and do what the corporation was doing and then you don’t get any advantage from it.

My feeling about ESG investing is that too much of it, as far as I can see, is investment companies taking advantage of investors. If a pension fund adopts an ESG policy, that means that they’re going to reduce the return of the fund. They should have to get investors’ permission to do that. In America, it’s very difficult because ERISA [Employee Retirement Income Security Act] rules require pension managers to maximize returns.

Where I am really concerned is people’s retirement. If people are moving their money to ESG without fully understanding the reduction in their return, I think that’s an issue. If you make, say, a 1% lower return over your lifetime, that translates into a hell of a lot less money for retirement. And if people are not making that decision in an informed way, I think that’s a very big concern.

I’m not a great fan of people saying, “Well, we’ll leave it up to corporations to fix society’s problems,” because that’s costly for the corporations, and costly for the shareholders. That is not to say that an oil company isn’t doing stuff that hurts society. But to fix that problem, you need the government. It’s government’s role to put in place pollution taxes. Then you can incentivize shareholders to do the right thing. But to just expect them to do the right thing is just naive as far as I’m concerned. — Told to Alexander Gelfand

The events of the past year, especially the collapse of the cryptocurrency Terra and the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, have made it clear that cryptocurrencies and private stablecoins need proper regulation. Privately issued stablecoins pegged to the value of the U.S. dollar have reached maturity on crypto trading exchanges but are hardly used at all in the real economy. In the future, stablecoins might play a useful role.

Other improvements in digital payments are on the way. Later this year, the Federal Reserve will release FedNow, a system for making speedy payments from bank account to bank account that will allow people to transfer money instantly, 24/7 and 365 days a year. It remains to be seen if FedNow will become as efficient as a central bank digital currency, but it may take the U.S. a decade or more to develop and deploy a CBDC.

The Fed has said that it won’t make any decision on a CBDC without direction from the White House and Congress. Many commenters fear that a CBDC will infringe on their privacy because the Fed could keep data on everyone’s payments. China has done just that with its own CBDC, called eCNY. Americans would not stand for that. If the Fed does deploy a digital dollar, I am confident that it will not store private transactions data.

In nations that have introduced CBDCs, however, usage has been low. For example, the People’s Bank of China has piloted eCNY in 26 cities. Total transactions in 2022 were on the order of about 150 billion yuan, much less than the 100 trillion yuan total for just one of China’s private payment services, Alipay. The total amount of eCNY held in wallets at the end of 2022 was only 0.13% of China’s official money.

Americans, especially those with low incomes, would benefit from a much more open, interoperable, and competitive payment system. While an official digital dollar might one day allow that, the nearer-term potential lies mainly with fast bank-railed payment services like FedNow. Unfortunately, however, each bank will probably choose its own way to provide FedNow services to its customers.

A better approach is to mandate payment apps that meet a common standard of interoperability. Brazil did that with its fast-payment service Pix. Because of that, Pix has become enormously popular. Since its introduction in 2020, almost 100% of adults in Brazil are using Pix. As a result, it has significantly improved financial inclusion. About five million households got bank accounts in order to use Pix. And about five million additional households that had used their bank accounts primarily to convert their wages into paper money are now using them to make digital payments with Pix.

Politically, the U.S. has had a hard time with telling banks how to provide payment services. Moreover, regulators seem concerned that if banks are forced into greater competition by a common payment app, then bank profitability and lending would decline.

I’m not convinced. While greater competition for payments might make banks less profitable, this has not happened in Brazil, where Pix has caused payment services provided by banks to soar. Because the current structure of the its market for deposit-taking and payments is inefficient, the U.S. should experiment with better approaches. Disruption is not necessarily bad. FedNow, and eventually a digital dollar, could offer Americans much more efficient payment services and bring many low-income Americans into the digital financial system. — Told to Edmund L. Andrews

Experts Discuss the State of U.S. Banking After the Silicon Valley Bank Collapse

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.