Arjay Miller was the fourth dean of Stanford GSB from 1969 to 1979.

It is characteristic of the man that when faced with urban riots in Detroit in the 1960s, Arjay Miller readily acknowledged he had no immediate solution — and then responded with a brilliant idea, the creation of an urban management program that would develop leaders with a business background who could rise to meet the social challenges of America. This idea became reality at Stanford Graduate School of Business when Miller made it a condition of his taking the helm as the fourth Dean of the school. The Public Management Program, founded in 1971, was the first of its kind in the country and has gone on to produce many distinguished graduates. Accepting challenges and finding innovative solutions was a lifelong habit of Miller, who died on November 3, 2017, at the age of 101.

Arjay Miller’s life and experiences spanned decades, and his professional expertise in managing institutions and organizations included not only business schools (though that is what he is known for in this corner of the Stanford campus), but other organizations as well. His approach to managing was, as he was himself, down to earth, humble, and caring about the people in his organizations — not a hint of a top-down approach. “The most important ingredient in organizations and in management is your people,” he said, a view which is equally applicable to private and public organizations, as well as to educational institutions.

His long life included years of service in the corporate world (as a member of the board at Wells Fargo, for example), but beyond that and throughout his career, Miller’s recognition of a greater good beyond himself shaped the paths he took. His emphasis on social consciousness, accountability, and higher values beyond the individual bore fruit in his management of organizations — whether responding to problems as a leader of a multinational corporation or leading new initiatives at a local university. Undaunted by challenges and pragmatically aware of real-world conditions, his vision for the future of business schools and management education was inextricably linked to a broad vision of civic improvement. Appreciating the enormity of the task, Arjay had been heard to say, “Making money is the easy part — making the world a better place is the hard part.”

The ability to see the world as it is and the instinct to try and make it a better place are just a few aspects of the legacy of Arjay Miller, who served as Dean of Stanford Graduate School of Business from 1969 to 1979. As one might expect, Miller was shaped not just by the content of his own contributions and experiences but by significant external events as well. He succeeded by being able to channel his energy toward finding ways to understand and solve problems, not just in organizations under his purview but in society as well. His values had their roots in rural Shelby, Nebraska, where Rawley John Miller Jr was born on March 4, 1916. (He acquired ‘Arjay’ courtesy of his sister, who assigned him the name, a combination of his father’s initials, when he first entered school.) Originally emigrating from Germany, Arjay’s forebears had moved across America to settle in the rich farmlands of the Midwest. Growing up on a farm taught him a respect for hard work, and farm values stayed with him throughout. “A farmer is like a CEO,” he once mused, reflecting on his own background.

Graduating from UCLA in 1937 with highest honors, Miller enrolled in the PhD program at Berkeley, an academic experience that would stand him in good stead at Stanford GSB. Drafted into the Air Force in World War II, he became one of the famous Ford ‘Whiz Kids,’ ten young veterans (including Robert McNamara, future Ford President, Secretary of Defense and lifelong friend) who were offered jobs at the company after the war. As Arjay told it, Henry Ford II assembled them in a room, plunked down a piece of paper and said, “Just put your name down, when you can start and the salary you want!” This unique group has since been credited with dramatically turning the company around in the post-war years; for Miller, it helped shape his views of managing organizations as well as seeing the importance of education of management.

Rising through the ranks, Arjay assumed the presidency of Ford in 1963, only to be faced with new challenges confronting the automotive giant in a time of great social transformation. Ralph Nader’s famous indictment of the industry, Unsafe At Any Speed, required Arjay and other industry chiefs to travel to Washington to testify. He realized that he and his executive colleagues were behind the curve. “We blew it,” he recalled in a 2000 interview. Just a few years later, when he and other business leaders in Detroit were frustrated by civic unrest, he honestly assessed the situation and grasped that there had to be a better balance between corporate interests and social responsibility. This realization eventually helped lead to Stanford’s Public Management Program, designed to educate managers not just for the private sector but for public sector organizations as well, expressing his belief that business was not just about maximizing short term profits.

One fascinating aspect of Miller’s Ford years is that, although many might see a tension between the emphasis on systems analysis intended to optimize resources in organizations and the social aspects, for Miller those were not contradictions but two sides that needed to be integrated, a balanced approach which influenced his instinct to evolve not just the Public Management Program but also an emphasis in the teaching of values and ethics at Stanford GSB as early as the 1970s.

Miller’s coming to Stanford was motivated in no small part by the influential figure of George Leland Bach. Miller knew about Bach at Ford, when he decided that the Carnegie Mellon Graduate School of Industrial Administration, where Bach was founding dean, was the source of the best and brightest students. Miller subsequently relied heavily on Bach’s friendship and advice at Stanford.

In 1969, through the involvement of Bach, Miller was approached by Stanford GSB to succeed legendary Dean Ernie Arbuckle, who had decided to “repot” after 10 years at the helm. Arbuckle had transformed the school, setting it on a path to become a great research institution, and whoever followed him would have big shoes to fill. It is a singular tribute to Arjay that he did so, with unqualified success. “I consider myself very lucky. I arrived at [Stanford] GSB at just the right time,” Miller later recalled. “Dean Arbuckle had built a solid foundation for the continued progress of the school.” As longtime friend and colleague James Howell put it, “Arjay had a tough act to follow, but he held his own.” He did more than hold his own. Characteristically modest, Miller was fond of pointing to his collaborators in the work, but it was his own firm hand that kept the School on an upward path. Stanford President Richard Lyman paid tribute to this fact when he remarked at Miller’s retirement in 1979, “The entire university is indebted to Arjay Miller for his leadership in that rise to greatness that can so easily be made to appear an inexorable part of some natural process but which, of course, could have only happened with inspired direction from the top.”

Arjay’s enthusiasm was no doubt responsible in attracting key faculty to Stanford GSB. David Montgomery, the Sebastian S. Kresge Professor of Marketing, Emeritus recalled Arjay’s personal enthusiasm over the idea of the public management dimension, and how it helped him decide to locate his own career at Stanford. “I want to work for this guy,” Montgomery decided, adding “He’s aces in my book.” As Dean, Miller hired scholars such as Henry Rowen and Alain Enthoven, with experience in applying analysis to social issues and government. He worked side by side with Lee Bach, who brought experience from Carnegie to bear in re-organizing Stanford GSB in the image of the ‘New Look,’ an approach with an emphasis on academic excellence in management education that is associated with the Ford Foundation and the influential 1959 ‘Gordon-Howell’ report (by Aaron Gordon and James Howell). Much of the New Look in business schools was about building a foundation of analysis and rigorous scholarship. But that did not mean neglecting real-world management problems in society; on the contrary, business school researchers could be inspired by those to use analytic and intellectual perspectives to help understand and possibly solve them, thus helping to integrate difference sides of the coin in what is sometimes called ‘balanced excellence.’

The New Look and the approach of balanced excellence became guiding principles as first Arbuckle and then Miller concentrated on fostering both strong research and teaching components at Stanford. Arjay in his own life always modeled a sort of balanced excellence, blending business savvy with a firm grasp of academic priorities. Indeed, that was central to Arjay’s vision, and he found balanced excellence to be not just an approach to business education, but a way of life, too. The mixing of academic disciplines with each other and with practice was not a surprise to him; after all, real-world problems don’t stay confined within academic categories. When, for example, he realized that money donated to the School was being substantially retained by the University, he vigorously appealed first to Stanford President Pitzer and then to his successor Dick Lyman, with the result that Stanford GSB became a ‘formula school’, an arrangement that has ever since allowed it to keep a larger share of what it has raised.

Arjay always loved to meet and talk with students. One group of students started a beer-drinking club dubbed the ‘Friends of Arjay Miller,’ FOAM, which continues to flourish today. Another group formed a Fifties-style rock band, calling themselves ‘The Arjays.’ When it came time for a publicity shoot in 1979, one of the band members, Blake Winchell, knocked on Miller’s door. Would the Dean be willing to pose with them in the conference room? Arjay did, grinning, with thumbs up. Someone later hung a print of this photo in a cabin at the Bohemian Grove.

Married for 70 years to his late wife Frances, he enjoyed the company of a growing family, including six great-grandchildren, as well as a worldwide network of friends. At his home in Woodside he took great pride in pointing out his collection of Native American art, as well as memorabilia from his Ford years. He long retained a fondness for gardening.

Arjay was also a great storyteller — but then there have always been stories told about the man himself. James Van Horne, A.P. Giannini Professor of Banking and Finance, Emeritus talked about the time Miller was a director at Wells Fargo Bank, and the bank was discussing the extensive group of international branches that they had developed over the previous ten years. With characteristic candor Arjay spoke up. “I bet we make more money in the city of Modesto than we do in the entire international department. You have an ‘MBA’ problem – Mexico, Brazil and Argentina!” The CEO said that can’t be true, but that he would check. Sure enough, the bank did make more money in the California city – which led the CEO to shut down the entire department and focus on domestic business.

Miller continued to believe in the importance of public management and social engagement and the heightened responsibility of the Graduate School of Business to respond to the current issues of the day. In recognition of the 90th anniversary of the school in 2015, he noted, “We’re becoming increasingly known as the business school with a conscience. I like that. Keep up the good work!” He remained active in the life of Stanford GSB community, as when he dropped by to help celebrate the Arjay Miller Scholars, the academically highest ten percent of a graduating MBA class.

The worldwide reputation of Stanford GSB has continued to grow over the years into the premiere institution it is today, but at its core one can still sense the guiding vision of Arjay Miller. As former Secretary of State and longtime friend George Shultz wrote, “The Graduate School of Business is one of the world’s best, Arjay, thanks in large part to you … remember that this magnificent school has been built on the foundation you created.” Miller insisted much of his life was just “luck” — but friends and admirers knew otherwise.

By Mie Augier and Paul Reist

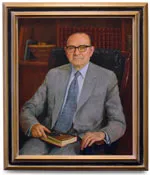

Story Behind the Book in Arjay’s Portrait

In the official oil portrait commemorating his years as Stanford GSB’s dean, Arjay Miller sits with his hand resting on a book titled Marriner S. Eccles, Private Entrepreneur and Public Servant. It well may be the only book ever published by the school but — as with most things Miller created during his tenure — it has an interesting story. Eccles, a banker and industrialist from Utah, served as governor of the Federal Reserve Board under President Franklin Roosevelt and was an author of some of the major banking reform bills of the 1930s. Miller was president of Ford Motor Co. when he first met Eccles at a conference in the 1960s, and the two became good friends. Miller eventually accepted Eccles’ invitation to serve on the board of his firm, Utah International.

After becoming dean, Miller, always a man of direct action, was trying to recruit Alain Enthoven to the business school faculty and thought an endowed chair might help close the deal. “They told me I was wasting my time because Eccles had said he would only give money to Utah,” Miller recalled. He approached Eccles, who demurred. “Marriner,” Arjay enthused, “you’re bigger than Utah!” Eccles established the chair. Miller then decided it would be good for Stanford to publish a biography of Eccles but grew frustrated at the slow process as Stanford University Press debated how to move forward. “I decided, well, the business school can publish a book, and we did.” Enthoven became the first Marriner S. Eccles Professor of Public and Private Management in 1973.

- Speech to the American Finance and American Economic Associations, December 29, 1968

- Featured article in Stanford Business magazine, May 2000